It’s the morning of March 31st, 2014, and the Google Maps team is about to release its April Fools’ Day gag to the world.

It wasn’t the first time this team had goofed around with an April Fools’ day joke. Google, as a whole, goes wild on April 1st. Maybe it’s for the resulting publicity. Maybe it’s to make the brand seem a little more fun. Maybe it’s to give employees a creative outlet that doesn’t seem so mission critical. It’s probably a mix of all three.

Google has used the first of April to “launch” everything from morse code keyboards, to AI-powered garden gnomes, to a translator for talking with your pets. They’ve “announced” that the company would be switching to Comic Sans as the default font across all of its products, and once spent the day suggesting that, despite whatever you might be searching for on YouTube, you probably meant to search for Sandstorm by Darude.

Most of the gags come and go (excluding Gmail, of course, which everyone thought was a joke thanks to its April 1st launch timing.) In most cases, everything is reset back to normal and everyone moves on.

This one would be a bit different. Within the next few hours, the wheels would be in motion for the product that became Pokémon GO.

This is Part 2 of our EC-1 series on Niantic, looking at its past, present, and potential future. If you haven’t read it, you can find Part 1 here. The reading time for this article is 31 minutes (7,900 words)

The joke that inspired it all

By April 2014, Niantic was still over a year away from its spinout of Google. At this point, it’s still Niantic Labs, an “autonomous unit” operating under Google’s roof.

Join 10k+ tech and VC leaders for growth and connections at Disrupt 2025

Netflix, Box, a16z, ElevenLabs, Wayve, Hugging Face, Elad Gil, Vinod Khosla — just some of the 250+ heavy hitters leading 200+ sessions designed to deliver the insights that fuel startup growth and sharpen your edge. Don’t miss the 20th anniversary of TechCrunch, and a chance to learn from the top voices in tech. Grab your ticket before doors open to save up to $444.

Join 10k+ tech and VC leaders for growth and connections at Disrupt 2025

Netflix, Box, a16z, ElevenLabs, Wayve, Hugging Face, Elad Gil, Vinod Khosla — just some of the 250+ heavy hitters leading 200+ sessions designed to deliver the insights that fuel startup growth and sharpen your edge. Don’t miss a chance to learn from the top voices in tech. Grab your ticket before doors open to save up to $444.

They’d launched Field Trip, which proved to the team that there was something to this idea of focusing around real world points of interest, but didn’t seem to keep people coming back. They’d followed up with their first game, Ingress, which had a dedicated following but hadn’t made them very much money.

“Niantic was trying to figure out what was next, and what we should do.”

That’s Masashi (or “Masa”) Kawashima. He runs Niantic’s operations in Asia, having joined to grow Ingress in Japan at a time when the country was around 25th on the list by playerbase. Nowaday’s it’s number one or two, depending on which phone platform we’re talking about. His passion for Niantic’s games runs deep; he rarely stops smiling when talking about them. Every question I ask is answered with a story, and each one is packed with a million details. At no point am I tempted to stop him.

“We were brainstorming,” he continues, “but we just hadn’t found a good idea yet.”

The inspiration they needed would come from an old friend.

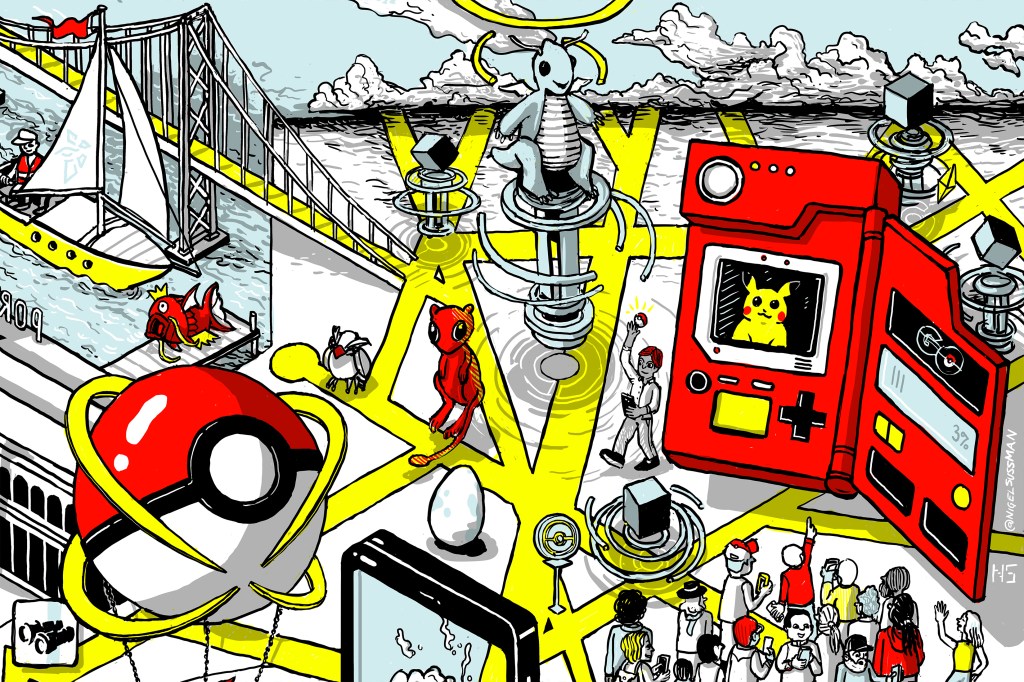

For April Fools that year, the Google Maps team had filled their virtual rendition of the world with Pokémon. Zoom around the map, look for Pokémon. Tap a Pokémon to catch it, adding it to your Pokédex. Catch all 151 and the company would send you a Google business card with your name on it under the title of “Pokémon Master”.

The interactive integration into Maps was fun, but it was the accompanying announcement video that caught Masa’s eye.

“It was real people, looking for Pokémon in a field,” says Masa. “They were in the desert, looking for sand Pokémon, or at the ocean, looking for water Pokémon. I saw that video and just went ‘Oh!’”

This was it. This was their next game.

He ran to Niantic Labs boss John Hanke to show him the video. John loved it, so Masa started looking into who had created the Pokémon gag for the Maps team. Google wouldn’t go anywhere near a mega property like Pokémon without the many necessary stamps of approval from rights holders, so whoever made all this clearly had the right connections.

Masa didn’t have to look far.

The engineer who led the April Fools’ Day project was a young man named Tatsuo Nomura, and Masa already knew him. They’d worked together years earlier, when Masa was a webmaster at Google Japan.

Tatsuo is a geek’s geek. I’ve bumped into him a few times over the years and, every time I can recall, he had at least one gaming icon or another hanging from his body to silently shout his interests to the world; a Zelda pin on the strap of his bag, or a tiny plush Eevee dangling from his hip. You can still find his name on the original blog post announcing the April Fools’ joke. His name signed the personalized letters accompanying the aforementioned “Pokémon Master” business cards Google sent out.

“I caught up with Tatsuo that night,” Masa says. He told Tatsuo what they were brainstorming, and asked how they might be able to move things forward.

As luck had it, Tatsuo was heading back to Japan for some interviews with the local media about Google Maps’ April Fools’ joke. Along the way he’d be meeting with Takato Utsunomiya, producer on dozens of Pokémon titles (and nowadays the COO of The Pokémon Company.) They only talked about the Niantic concept briefly, but it was enough to get the ball rolling.

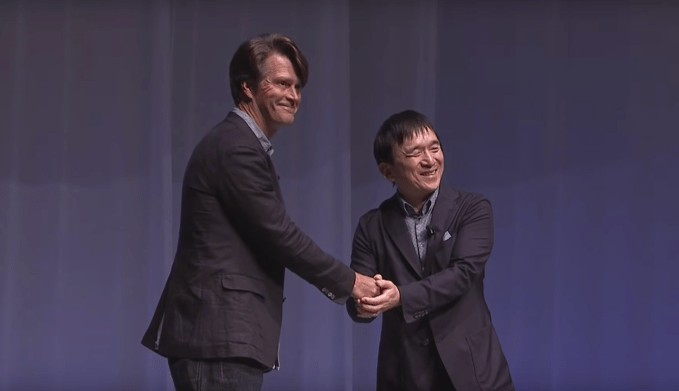

Within weeks, Masa, John, and Tatsuo (still officially a part of the Google Maps team) were together on a plane to Tokyo. They’d be meeting with the President of The Pokémon Company, Tsunekazu Ishihara, and other key executives.

“Masuda-san was there,” says Masa, beaming. Junichi Masuda is a founding member of the Pokémon team; he’s been composing music, building tools, and directing new Pokémon titles from the very beginning.

“We pitched on how [our companies] could make a harmony,” says Masa. “How we could make this dream together.”

In the end, Masa says, it was “a nice pitch”. They didn’t leave certain of where things would go next, but did end by asking Ishihara, Masuda, and the others in the room to spend some time playing Ingress.

They didn’t have to ask twice. Some of them had started playing even before the pitch. At least one of the executives had already gotten super into it.

“Three days later,” says Masa, “I got an email from Mr. Ishihara.”

“He’d become some really high level” Masa says proudly. “He’d shoot me a bunch of really hardcore questions, like, you know, ‘if I insert the resonator from north to south, is there any sort of millisecond difference?’”

By June of 2014, The Pokémon Company was at Google’s US headquarters figuring out how to make Pokémon GO a reality.

Ingress, but simpler

It’s not uncommon to hear Ingress players suggest that Pokémon GO is just a simple, cartoony version of their preferred game.

The jab makes sense, in a lot of ways. While Niantic’s two games have much in common — you play by moving around a map, interacting with real world points of interest — Pokémon GO is a helluva lot simpler than Ingress.

In Ingress, you’re hacking portals, coordinating efforts to take over massive chunks of the world, and trying to keep up with a rich, complicated Sci-Fi storyline as events unfold between the two warring factions. It’s a game perhaps best learned next to a friend who already plays.

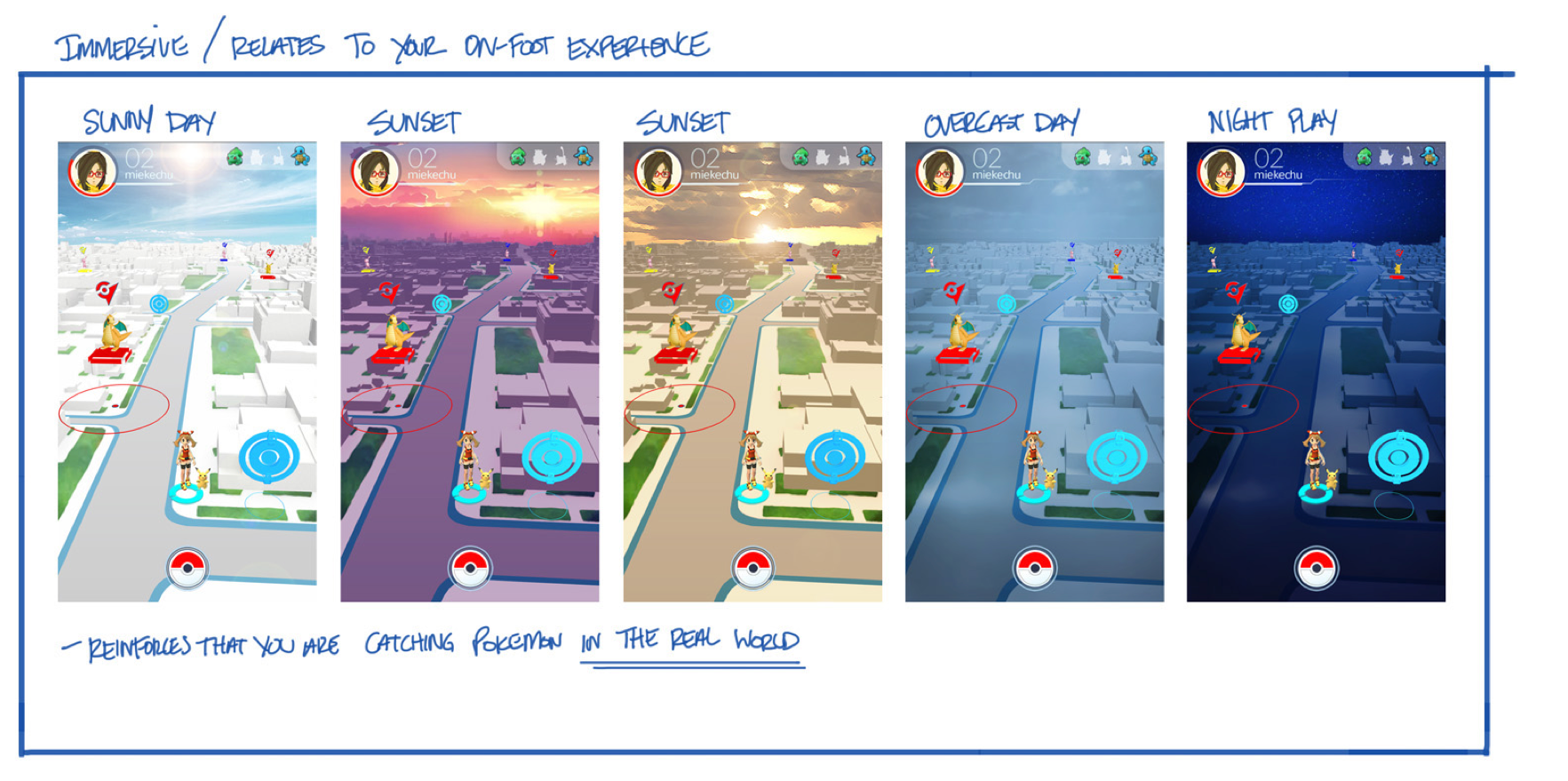

In Pokémon GO, you catch Pokémon. The game has gotten a bit more complicated over time, but the original goal was to make it as simple as possible.

That call, says Masa, came from Ishihara before work even began. After months of playing Ingress, Masa says that Ishihara found Ingress’ approach “too narrow, too niche, and too hard for players.” But if they could simplify it for a more casual audience, they’d have a hit on their hands.

So that was it: they’d build Ingress, but simpler. Instead of walking around to pick up energy needed for in-game actions, you’d pick up Pokémon. Instead of hacking portals and working with teammates to control territories, you’d spin Pokéstops. Whereas Ingress might challenge a new player to walk a few blocks to find their first objective, a player’s first Pokémon would basically spawn at their feet. Work officially began.

The leap of faith

As the end of 2014 approached, Pokémon GO was well underway. They had The Pokémon Company on board, and their shared vision was starting to come together.

But Niantic Labs was almost out of runway.

As covered in Part I, the team had already decided to spin-out of Google and form a new company. They were knee deep in negotiations with Google, figuring out exactly how a spin-out would even work. Google would give them a few million for a stake in the new Niantic, Inc. But if they were going to finish Pokémon GO, Niantic would still need to find more money. The problem? Few VCs seemed to want any part of it.

Meanwhile, the Niantic team was shrinking. Even if the team could raise all the money they wanted, not everyone was about to leave Google for a job with this little startup. People have kids, and debt, and mortgages to pay. By the time the spin-out was through, the team would drop from around 80 employees to less than 40.

And they still had to tell The Pokémon Company what was happening.

“Pokémon GO was really the future of Niantic,” says Masa. “After the spin out, we’re going to be a very small and risky company. [They] are thinking that they’re working with Google, a big company, a global company. But if it’s this unknown company? Just kind of small, maybe 40 people? They might stop working with us.”

Masa pauses, some of the stress from that time seemingly bubbling back up and breaking his smile for the first time I’d noticed.

“We must make Pokémon GO happen to survive,” he says. “In order to do that, we needed Tatsuo.”

Even this far into the process, Tatsuo — the man who inspired it all with his Google Maps April Fools’ joke, and who’d forged the connection with The Pokémon Company that let it move forward at all — wasn’t officially a part of Niantic Labs. He was still part of the Google Maps team. With the spin-out looming, work visa details complicated the conversation. By the end of the year, they’d ironed them out enough to bring Tatsuo on board.

“[Tatsuo] was the strong bridge between The Pokémon Company and us,” Masa continues, “He had grown up with Pokémon. Mr. Ishihara was impressed. It’s 20 years since Pokémon appeared in the world, and he’s starting to see this first generation of Pokémon kids becoming engineers and building this thing. From the bottom of my heart, I think he feels that this seed has grown, and now it’s [producing] this fruit.”

With Tatsuo signed on, it was time to go back to The Pokémon Company. Time to figure out if this project, “the future of Niantic”, could even continue.

“Their first reaction was just ‘… What?’” Masa says, emulating the perplexed stares he saw that afternoon.

“But then,” he continues, “Ishihara-san just said ‘… Is there any way we can help?’”

After all their worries that The Pokémon Company would pull the plug, it ended up taking the completely opposite approach. Not only would The Pokémon Company continue working with Niantic, but they’d help to make sure Niantic had the money to pull off this spin-out.

Nintendo, which owns a substantial stake of The Pokémon Company, would help, too. After the meeting with Ishihara, the Niantic team traveled to Kyoto to meet with Nintendo’s President and CEO, the late Satoru Iwata. In his time as president, Iwata had led the charge behind the Nintendo Wii — a console that used motion controls to get its players moving and exercising — so he got what Niantic was going for with Pokémon GO.

“He felt a lot of empathy towards us,” says John, “and this whole notion of games that have a good impact on society. He was really proud of what he had done with the Wii, and was really proud of what they’d done with Wii Fit.”

“That meeting was pivotal,” he continues. “We absolutely needed it. We were pretty far along in this process, and we were not getting any VC to step up as a lead at that point. And they said they would do it”.

Iwata quickly committed to investing in Niantic. It was one of the final decisions he made as the leader of Nintendo; in July of 2015, Satoru Iwata died of complications from a bile duct growth.

Between Google, The Pokémon Company, and Nintendo, Niantic raised $30M to get this spin-out done and finish Pokémon GO. The deal was “tranched”, meaning Niantic wouldn’t get it all at once. They’d get $20M upfront, and the other $10M if the game hit certain milestones and proved to be a success (spoiler: it did.) It’d be enough money to let them move forward, but it was deliberately staged in such a way that they had to keep moving to stay alive.

The months that followed were a flurry of paperwork; they were wrapping negotiations with Google, finalizing the investments, and figuring out just how many employees could (or would) come with them. Employees turned over unvested Google equity in exchange for a stake in Niantic.

In October of 2015, Niantic Labs officially spun out of Google and became Niantic, Inc.

“We have our game. We have our IP. We have our 30, 35 person team,” John says. “Let’s go ship Pokémon GO, and by god, we need to do it in 24 months, because that’s when our money runs out.”

The launch

In spinning out of Google, Niantic had lost roughly half of its employees.

When you lose half your team, you don’t just lose half your productivity. A huge chunk of your knowledge base goes with them, and the effects ripple out. Pokémon GO was already 2/3 done, but now much of the crew that laid down that codebase was gone, having stayed at Google.

John Hanke estimates that less than half of the 35 or so people who came over in the spin-out were engineers. The rest had their own key roles, like design, marketing, and events — but in terms of engineers that would be coding the game? “Maybe 15 people,” John says. That’s a small dev team to be building a game like Pokémon GO. And they had to keep Ingress running, too.

But they got it done, to a point. They’d end up shipping the game just 9 months after spinning out of Google, leaving themselves ample time to course correct if necessary.

Even focusing on that early vision of a simpler Ingress, they had to shelve some things for later. Signature features from the Pokémon series, like trading and battling Pokémon, would have to be built out down the road. User confusion during play-testing had the team changing things down to the last minute. Huge parts of the game, down to things as fundamental as how players would find nearby Pokémon, would need to be completely rebuilt from scratch in the coming months. But the core of the game was ready.

On July 6th, 2016, Pokémon GO launched.

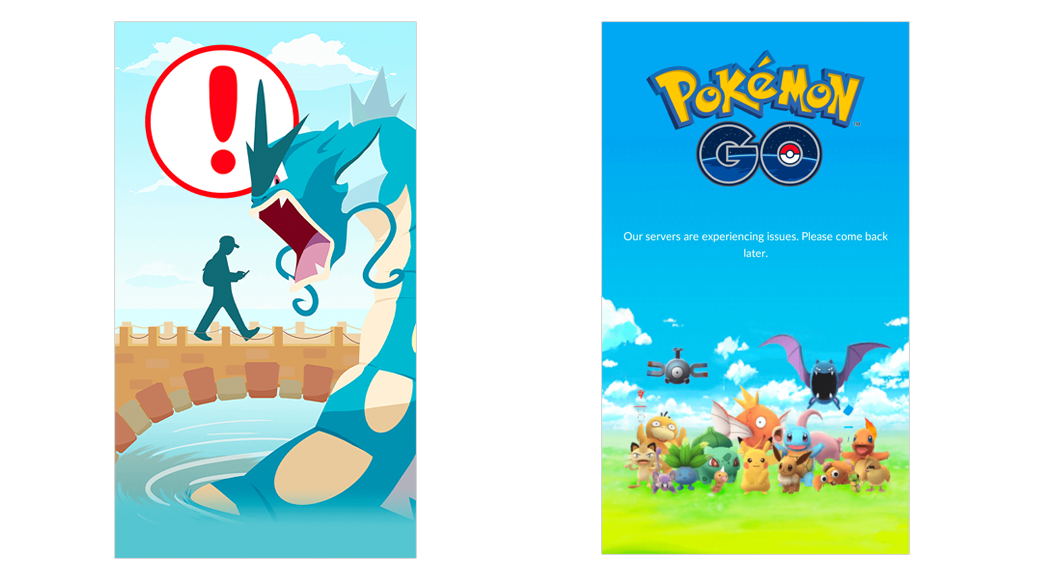

Everything immediately broke.

Overwhelming demand rammed headfirst into Niantic’s first draft get-it-done server architecture, and the game went down hard. If you played Pokémon GO in its early days, you probably remember: if you could even sign up for an account in the first few days, you were one of the lucky ones. Once you were in, you might get a few solid minutes of walking around before the servers choked and the game kicked you out. Most early players spent more time staring at the game’s loading splash screen than actually playing.

Niantic’s engineering team had thought to roll out the launch country-by-country (starting in Australia, New Zealand, and the US) to limit how many users could sign up at once, but the servers still couldn’t keep up. Every time the team thought they’d got it under control, they’d roll it out to a few more countries. Every time they rolled it out to new countries, everything broke again.

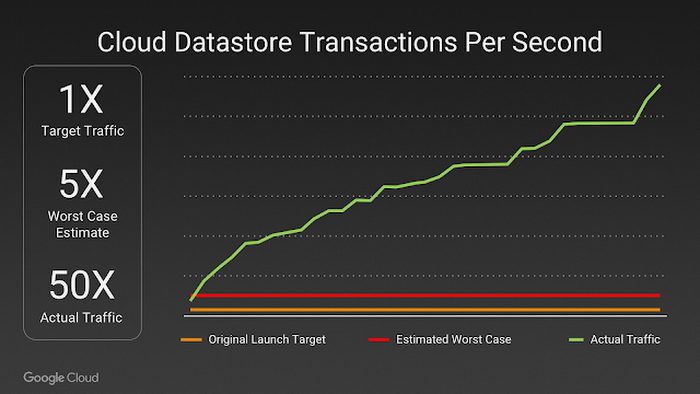

Masa grabs a pen, and starts drawing a graph on a huge whiteboard nearby.

“This is the line of what we expected,” he says as he streaks the pen across the bottom of the board. “This was our ‘worst case’ scenario,” adding a line just a few inches above. “What happened was more like this,” he says, reaching his arm to its fullest extent, the line barely staying contained on the board.

At its peak, traffic was about 50x any of Niantic’s worst case projections. Rather than figuring out what to add to the game next, Niantic suddenly had to focus on just keeping the game working.

The launch schedule shifted. Take Japan, for example. As the birth place of Pokémon, it was inevitable that demand in Japan would make all of the other launches seem like a warm-up. Niantic intended to launch Pokémon GO in Japan on July 16th, making the announcement at a massive gathering of 15,000 Ingress players in Tokyo.

They flew John out to make the announcement, but the servers just weren’t ready. John had to limit his announcement to just reiterating that Pokémon GO was coming to Japan “soon”.

Server issues continued to plague the game for weeks post launch, coming to an end only after Niantic called in an assist from an old colleague: Google CEO Sundar Pichai. While Niantic was no longer a part of Google by this point, Google is an investor. Perhaps equally important, the entire thing is running on Google’s Cloud engine. A worldwide craze floundering on their engine isn’t a very good advertisement for potential customers.

The Google Cloud team worked with Niantic to figure out the scaling issues, with Google firing up “many tens of thousands of cores” to keep GO stable. In a blog post outlining the efforts, a director at Google Cloud calls it the “largest Kubernetes deployment” its engine had ever seen.

On July 22nd, the game finally launches in Japan. Things got a little shaky when everyone in Tokyo got off work in the evening, Masa tells me — but for the most part, it’s stable.

Pokémon GO takes over the world

The launch of Pokémon GO was, for lack of a better term, absolutely bananas.

If you lived in any major city when GO was released, I don’t have to tell you that. It was like a virus had hit the population, the symptoms of which included staring intently at your phone, wandering aimlessly around parks for hours on end, and shouting “THERE’S A SNORLAAAAAAX!” before sprinting away.

For months after release, you couldn’t step outside without seeing someone playing the game. Businesses put signs on their windows to encourage players to come in, offering special deals to anyone who came in and showed their Pokedéx. There were “pokécrawls” where thousands of players met up and hiked across their cities. People around the world were rocking Ash Ketchum hats and Pikachu onesies.

As with anything involving hundreds of millions of people, it had terrible moments. Crowds took over landmarks. There were stampedes. People fell off cliffs, and got hit by cars.

And there were privacy scares. An early build of the game asked iOS players signing in with Google accounts for “full account access”, which some took to mean Niantic could read your email. It couldn’t — but it was still a broader request than the game needed to make. Google confirmed that the game had only accessed data it needed (like user ID and email address details) and Niantic patched the game to instead request the “basic account info” it needed.

But none of that seemed to stymie the world’s interest.

But why? Why was it so popular?

It’s hard to pin the explosive fervor for the game on any one thing; it’s more like a storm of factors swirling together into something absurd.

There’s the fact that the game requires people to play in the real world (often in groups), leading others to wonder what the hell they’re all doing and maybe checking out the game for themselves.

Then there’s the underlying, fundamental concept. It’s just so easy to explain: “you’re catching Pokémon, but, like, in real life.” That’s all it took. If you had touched a Pokémon game before or grew up with the animated series, you were probably poking around the App Store to download it by the end of that sentence.

And then there’s the almost-too-perfect timing. The year GO launched also happened to be the 20th anniversary of the 1996 debut of Pokémon. Many of the people who’d grown up playing Pokémon picked it up to scratch that nostalgic itch, and, perhaps, introduce their kids to the series. It had the absolutely ideal timing for bridging generations.

Mash it all together, and you get a craze like the world has never seen before.

Even when the servers were on fire and completely failing, people seemed to just sort of stick with it. The concept just made too much sense. If it didn’t work now, people would try again in a couple hours. People seemed willing to hang around for what this game could be. Or maybe they just didn’t want to miss some rare Pokémon that could be right outside their house, if only they could log in.

And when the servers finally stabilized? For weeks, for months, it was just, well, nice. Strangers helped each other find Pokémon, sharing tips and rumors and bonding over the ones that got away. You could drop into a new city on any day, go to the biggest park on the in-game map, and find a couple dozen people who’d be happy to hang out. The height of GO’s popularity was a short-lived but oddly magical period of time.

But the game’s technical troubles weren’t over quite yet.

GO Fest goes down

One year after the launch of Pokémon Go, Niantic had mostly worked out the game’s kinks. They’d tweaked some things about the way the game itself worked, and had added about 80 new Pokémon to the game. The world’s fever for the game had broken; the stampeding mobs were mostly gone, but plenty of people were still playing. On any given day, GO was still hanging out in the iOS App Store’s Top 20 grossing games, with the game’s in-app purchases proving to be a solid revenue stream.

It was time to return to a concept they first tapped with Ingress: live, real-world events.

Pokémon GO had a bigger userbase than Ingress, so it needed a bigger event. Niantic would take over an entire park in Chicago, fence it off, and sell around 20,000 tickets for $20 a pop. It’d be sort of like a music festival — just, you know, without the music. Attendees would get the opportunity to catch Pokémon that didn’t normally spawn in North America, and would be the first in the world to face off against “Legendary” Pokémon — massive, ultra powerful monsters that take up to 20 people working together to capture.

It’d be called GO Fest.

“We felt like we had really turned a corner in terms of shipping features and demonstrating the ongoing success of the product, and we had the first GO Fest.” says John. “You were there, right? That was a tough day.”

I was there, covering it for TechCrunch. “Tough day” is a gentle way of putting it. Like a living incarnation of Pokémon GO’s launch a year before, everything broke the second it was meant to begin.

Logistical issues led to lines that stretched the block. With only a dozen-or-so entry turnstiles for many thousands of people, there was still a queue outside hours after the event kicked off at 9 am.

And then came the connectivity issues. Have you ever been to a massive concert and tried to use your phone in the middle of the crowd, only to find that nothing works? Your phone might swear that you’ve got perfect signal — and yet, no pages will load, and no messages will send.

Now imagine that, except that entire massive crowd — literally everyone there — is trying to use their phones to play the same data-intensive game. A game known to be sort of wonky on a stable connection, no less.

The problem was (at least) two fold. For one, phones tend to perform worse when you put more phones around them. More phones = more noise washing out the signal, and more bodies holding those phones means more obstruction between the phone and their respective cell towers. For two, most of those cell towers, even if you could connect to them, aren’t built to handle a sudden influx of thousands and thousands of people all trying to pull down data. Niantic had thought to roll in a few temporary cell towers, but they weren’t nearly enough.

No one at Pokémon GO Fest could actually play Pokémon GO.

The crowd booed, chanting “WE CAN’T PLAY! WE CAN’T PLAY!”. People threw things at the stage. People lined up to shout at the information desk. People sued.

Topics