In my previous essay on TechCrunch, I examined the profound challenges that confronted the computer engineers trying to fit tens of thousands of Chinese characters in a memory system designed to handle a much smaller alphanumeric symbolic system.

The engineering daring that led to the first Chinese personal computer

Now, I turn to the question of Chinese character output — monitors, printers and related peripherals — where still more challenges confronted engineers seeking to render Western-manufactured personal computers and computer peripherals compatible with Chinese character text.

While we call them “peripherals,” suggesting a sort of supporting role, they are in fact at the very center of computing in Chinese, from the extreme limitations that Chinese computing faced in the 1970s and 80s to the immense strides and successes it has experienced from the 1990s onward.

During the early rise of consumer PCs in the 1980s, no Western-manufactured personal computer, printer, monitor, operating system or other peripheral was capable of handling Chinese character input or output — not “out of the box,” at least. To the contrary, all of these devices exhibited the same kind of English-language and Latin alphabetic bias found in, for example, the early history of telegraphic codes and mechanical typewriters, as I’ve explored in my other research.

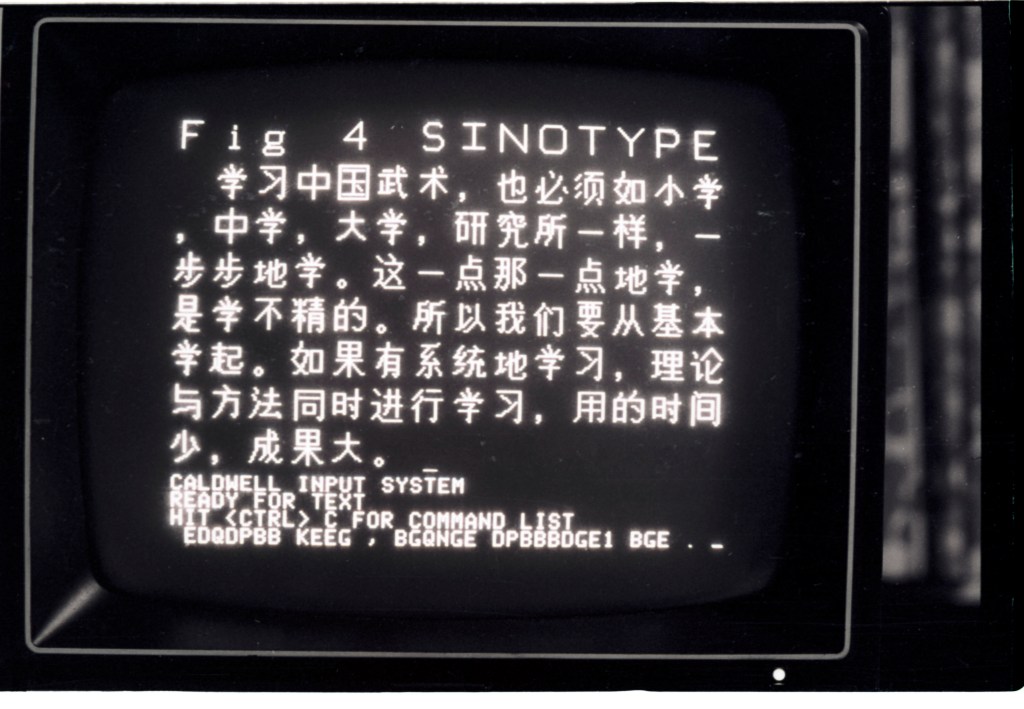

During the 1980s, what ensued in China and the Chinese-speaking world was a period of intense hacking and modding. Element by element, engineers in China and elsewhere rendered Western-manufactured computing hardware and software compatible with Chinese. It was a messy, decentralized and often brilliant period of experimentation and innovation.

Join 10k+ tech and VC leaders for growth and connections at Disrupt 2025

Netflix, Box, a16z, ElevenLabs, Wayve, Hugging Face, Elad Gil, Vinod Khosla — just some of the 250+ heavy hitters leading 200+ sessions designed to deliver the insights that fuel startup growth and sharpen your edge. Don’t miss the 20th anniversary of TechCrunch, and a chance to learn from the top voices in tech. Grab your ticket before doors open to save up to $444.

Join 10k+ tech and VC leaders for growth and connections at Disrupt 2025

Netflix, Box, a16z, ElevenLabs, Wayve, Hugging Face, Elad Gil, Vinod Khosla — just some of the 250+ heavy hitters leading 200+ sessions designed to deliver the insights that fuel startup growth and sharpen your edge. Don’t miss a chance to learn from the top voices in tech. Grab your ticket before doors open to save up to $444.

When we turn our attention to this broader ecology of computing — on printers, monitors and all of the other “stuff” needed to make computing work — part two of this series on Chinese computing spotlights two conclusions.

First, the dominance of alphabet-based computing — “alphabetic order,” as I call it — went far beyond the question of keyboards and computer memory. Like the typewriter before them, computing devices, languages and protocols were by and large invented first in English-language contexts and only later “extended” to other languages and to writing systems other than the Latin alphabet. To achieve even basic functionality, Chinese engineers needed to constantly push against the boundaries of off-the-shelf computing peripherals, hardware and software.

Second, I’ll dismantle the oversimplified idea of Chinese “copycatting” and “piracy” that has dominated, then as now, Western accounts of Chinese computing during this pivotal period in the late 1970s and 1980s. When encountering programs such as “Chinese DOS,” the knee-jerk reaction in the Western world has been to treat them as just more “Chinese knock-offs.” What this simplistic narrative fails to understand is that without the kinds of “forgeries” we will examine in this article, none of these Western-designed software suites would have worked at all in the context of Chinese character computing.

Dot-matrix printing and the metallurgical depths of alphabetic order

The first peripheral we need to examine is the printer — specifically, dot-matrix printers. From the standpoint of Chinese computing, the politics of dot-matrix printing began with the then-dominant configurations of industry standard printer heads — the nine-pin printer heads found in practically all mass-manufactured dot-matrix printers during the 1970s.

These commercial dot-matrix printers were able to produce low-resolution Latin alphabet bitmaps with just one pass of the printer head. This was not by accident, of course. Rather, the choice of nine pins was “tuned” to the needs of low-resolution Latin alphabetic printing.

The same printer heads, however, were incapable of printing low-resolution Chinese character bitmaps in anything less than two full passes of the printer head. Two-pass printing dramatically increased the time needed to print Chinese as compared to English and also introduced graphical inaccuracies, whether due to inconsistencies in the advancement of the platen, uneven ink registration, paper jams or otherwise.

Aesthetically, two-pass printing could also result in characters with differing ink densities on their upper versus their lower halves. Worse, in the absence of any mod, all Chinese characters would be at least twice the height of English words, no matter the font size being used. This created comically distorted printouts in which English words appeared austere and economical, while Chinese characters appeared grotesquely oversized. Such printouts also wasted large amounts of paper, with every document looking something like a large-print children’s book.

An example illustration of how these printer heads work is provided in this video, courtesy of the author: